Knowledge Organisers for Art in Primary Schools

By Paula Briggs

This article explores the current trend for using knowledge organisers in primary schools, and suggests alternative ways of thinking.

When I first heard people talking about a “knowledge-rich curriculum” I struggled to understand what they meant. I understood the words individually so could not understand why they made little sense to me, when taken collectively and applied to visual arts learning. I studied art at degree level and then later again at postgrad level and I have worked in arts education for over 25 years, and yet it never occurred to me to think of myself or my creativity as being “knowledge rich.” Of course I had picked up a fair bit of knowledge along the way, but that was not what was important to me – what was important was experience. I feel experience-rich. If I don’t know, I google, but there is no google (yet) to find experience.

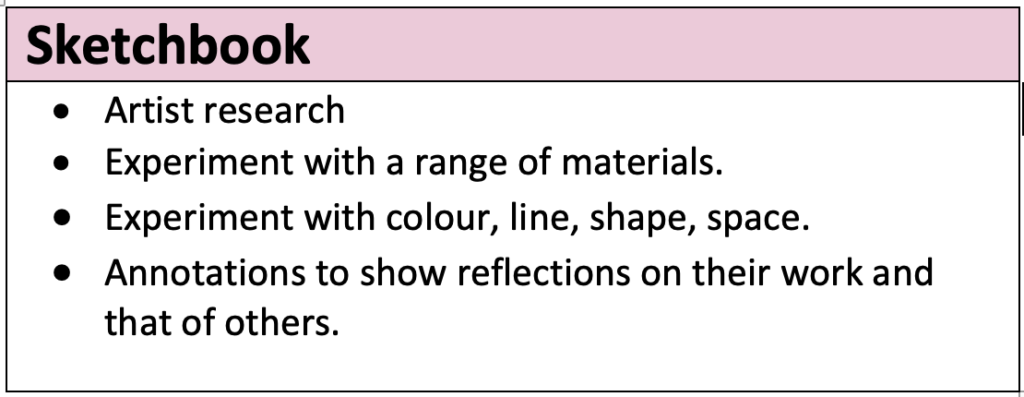

Increasingly, AccessArt finds ourselves being asked to give our opinion on the use of knowledge organisers in primary art. Schools send their knowledge organisers to us, asking us to help “build in more depth”, and we struggle with that. The knowledge organiser tells us little or nothing about how art is facilitated – and that’s what adds depth. Here’s an example taken from an organiser:

You can see how it says nothing about “how” (or why or what if, or how do you feel). The words and ideas are so distilled, they become meaningless. Knowledge organisers require this type of distillation, but we worry the focus on knowledge organisers is masking a number of more important issues, which are getting more and more hidden behind those distilled words.

We’ve seen quite a few examples and it feels like it’s time for us to tackle the question:

Is it ever effective or even desirable to “organise someone’s knowledge” in art?

That question is loaded on so many levels and we need to pick it apart, and in doing so we need to ask a whole load of other questions and check our assumptions before we move forward.

Let’s Talk about Knowledge

Q. Do we worship at the altar of Knowledge or Experience? Can we do both?

A. Yes, but we need to start with Experience.

When we work with a class of eight-year-olds, they soon become familiar with the word “chiaroscuro”. They like rolling the word around in their mouths and they learn what it means. That is a piece of knowledge – a piece of declarative knowledge – and I can see it appearing on a knowledge organiser. It’s a little golden nugget of knowledge offered on a platter of which everyone is proud.

But I would put that piece of knowledge on a paper aeroplane and fly it across an ocean compared to the experiential understanding of chiaroscuro that the children build through the drawing sessions. That I would hold very close.

Let’s think about how chiaroscuro might appear on a knowledge organiser. Perhaps:

“The treatment of light and shade in drawing and painting”, or

“Chiaroscuro was one of the techniques used by painters of the Renaissance to make their paintings look truly three-dimensional”, or

“Italian term which literally means ‘light-dark’”, or

“Artists who are famed for the use of chiaroscuro include Leonardo da Vinci and Caravaggio.”, or, if we’re lucky:

An image which shows an example of chiaroscuro.

These are examples of knowledge passed down from teacher to pupil.

Let’s think now about how the child might experience chiaroscuro through practical exploration.

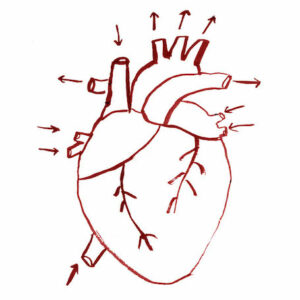

Maybe the child will explore charcoal, experimenting with how much pressure needs to be applied to make a “dark dark” or a “light light”. What happens when the hand is used to smudge the charcoal, or what happens when you introduce white pastel or draw on a dark ground? How does the energy of the mark making affect the mood created by the chiaroscuro? How can we use chiaroscuro to create a sense of drama, mystery or storytelling? How do we react to it as individuals – how does it make us feel? Can we use a torch to illuminate a scene in a cardboard box so we can work from a real life setting of dark and light? How about we dilute inks and use them with undiluted inks to create portraits? Can we use the white page as the light parts of the drawing?

Do you see the number of questions raised through the explorations above? Asking “what if”, exploring and sharing the revelation of what is discovered, IS the creative process. It is ongoing and never finished – the more you explore the more clues you find and the more journeys you are tempted to go on. Being given the “knowledge” without being enabled to experience it for yourself is a whole different process. Being given the knowledge is more finite, less deep, less rich, with an end point for you to “know”. In this sense knowledge can actually be limiting, not enriching.

The reality is, as artists we could spend a lifetime exploring chiaroscuro and we would never have finished learning. I don’t know many artists who would stand back and say “now I have a body of knowledge”, though they might say “now I have gained experience, insight inspiration, and understanding.”

Of course if a knowledge organiser is a summary of excellent experience, then great, but our instinct tells us; that is not often the case. Too often the knowledge organiser is used instead to hide behind – it can make it look like some serious, heavy weight ground is being covered, but we need to ask the question: What do we uncover in terms of experience when we look behind the knowledge organiser? That is the important thing.

So What of “Knowledge-Rich?”

There are of course elements of knowledge which a child should and will build throughout their experiential creative journey. There are terms to be understood, vocabulary to be used, techniques to be described. There are materials and artists and concepts and movements and ideas. But, and this is a big but, because declarative “knowledge” can be more easily distilled onto an A4 sheet in clear and concise terms, it means that this type of knowledge is suddenly given huge priority over the experience of actually making art. By definition, the experience is nowhere to be seen on the knowledge organiser.

Yet ideally, the experience of making art is THE most important thing; exploring materials, using tools, thinking through ideas and seeing how they change when made real, taking creative risks, understanding why things succeed or not, being exposed to new adventures, and the opportunity to practice, practice, practice, – let’s call it the “studio practice”, is the thing that we should be concentrating on at all stages of art education. It is through this kind of practical experience that children build (and own) their knowledge and without that practical experience that knowledge is just theoretical. It is a classic mistake made in many primary schools with many non-specialist teachers that art theory and art appreciation and art history become muddled with studio practice and the prevalence of knowledge organisers is making the situation more heightened and leads to studio practice becoming undervalued.

So, even if you are creating knowledge organisers in other subjects at Primary School, let’s not assume it is in our pupil’s best interests to “organise knowledge in art”. Because whilst we are busy organising knowledge, we are not thinking about HOW we enable experience, which is far more important.

Let’s Talk About Organisers

Q. Should we organise “Experience” then, instead of “Knowledge”? Shall we start a whole new trend (because let’s face it that’s what Knowledge Organisers are) around Experience Organisers?

A. The short answer: possibly not.

We’ve explained why we would like to encourage schools to think about replacing the word “knowledge” with “experience” when thinking about art in primary school. Now we would like to challenge the word “organise”.

Declarative knowledge is suited to a knowledge organiser, experience is less suited to being organised. Organising experience into a shared A4 doc tends to stifle opportunity and growth for individuals.

Let’s look at the key elements of a creative experience at any age or ability – the things we should be enabling and celebrating, and you’ll see they might not sit comfortably within any kind of organiser:

-

A personal journey – creative journeys might have the same starting point, and sit within a shared structure, but we want to see children owning their experience and able to move forward in diverse ways. This might mean one child gaining drawing skills from a project, and another child gaining literacy skills from the same project. One child drawing with charcoal, another using charcoal and pastel. Brave children (and brave teachers).

-

Open-ended learning – we do not want to see a class producing 30 identical end results (see above), so we need to take an open-ended approach. By nature this is messy, but exciting, liberating and not easy to define at outset. Try to control the journey too much and you will limit discovery and disrupt ownership. You might think you are doing one thing, but you end up doing another.

-

All experience is valid. Facilitating art is not about top down teaching. Instead it is about enabling an opportunity so that the child can discover for his or her self. Old truths are learnt again and again by us all, but we learn them in art for ourselves through experience.

The problem we have with the “organising” part, is that we don’t accept the creative experience can be “tidied” in a convenient format required by any kind of “organiser”, without losing integrity.

AccessArt would encourage schools to think again about using knowledge organisers in primary art, but if you still feel the need to use them, then let’s ask:

So, IF We Still Want To Use Knowledge Organisers in Art How Can We Improve Them?

-

Don’t muddle knowledge organisers with teaching plans. If the purpose of the knowledge organiser is to help parents and staff identify what will be covered, then perhaps it is a plan not a knowledge organiser.

-

If the purpose of the knowledge organiser is to help pupils recap and remember, then make sure it is written in language a child will understand. Remember not every one can “read” charts and grids. Think also about SEND requirements. For all children, make sure the content directly reflects what has been covered in class in such a way that the child can relate what is on the page to what they did in class (test this out: test the plan not the child;)).

-

Better still, involve the child in its’ creation (though see alternatives below).

-

Teachers should ask themselves: “What’s around the knowledge organiser? What scaffolding do we create to ensure a good experience to make the knowledge meaningful? How do we teach what’s on the plan? Once you start asking these questions the onus goes to how the teacher facilitates, rather than being placed on the child to accumulate knowledge. Take a look at all the experiences shared on AccessArt to see what scaffolding might look like.

-

Remember – we are talking about the visual arts – if you must have a knowledge organiser make it visual.

-

Your knowledge organisers should try to reference experience. They should be open-ended and outward looking. Make them less about finite points of knowledge learned and instead, make them question-based, encouraging the child to apply their knowledge by reflecting. See how you can use a Class Crit to encourage reflection and discussion.

-

Lastly, think about making your knowledge organiser a promise from the school to the child which the child can complete: “I have been given the opportunity to explore xxx and I learnt this yyy”

If We Have Been Persuaded To Leave Knowledge Organisers Out In Art, What Can We Do Instead?

If knowledge organisers are used to plan, share, recap and show then we are very lucky, because the visual arts offer lots of opportunities to do all those things (and far more) without resorting to a knowledge organiser. Here are the good old fashioned tools we have at our disposal:

-

Reference Material (displayed in books, websites, walls): The theme or area of study can be displayed in lots of ways.

-

Sketchbooks: Children (and staff) can use sketchbooks to plan, share, recap, reflect.

-

Conversation: One to one, group, peer, teacher: lots of ways to have conversations about the work which can help teacher check understanding and build experience. Notes can be made in sketchbooks as a result, alongside project work.

-

Art Work: The beauty of the visual arts: “It didn’t exist and now it does”

Key Takeaways:

Knowledge organisers tend to make art tidy, and the creative process is rarely so neat.

In art, we gain most knowledge through experience. Art is about exploration and discovery and art in primary schools should be about enabling that for the child, so that they can learn for themselves, with our help. Let’s think about how we can Enable their Experience rather than Organise their Knowledge.

Don’t assume any non-specialist or NQ teacher has the skills to understand the “how”. Direct them to our resource How Do Non-Specialist Teachers Teach Art?

Protect time spent in “studio practice” in which pupils learn through doing, and embed building their knowledge (history/appreciation/contextual). Question if the opportunities you provide for pupils are a balance of practical/theoretical skills and think carefully how they feed into (and off of) each other.

Ask yourself if knowledge organisers create a state of statis in teaching (same one used each year) and repeated learning? Is there space for innovation and reinvention each year? As soon as we have knowledge, we are at the end of that particular journey. Do they create statis in exploration too? Do they allow (celebrate) a pupil to diverge from the original plan because they have made a discovery?

Let’s try replacing a few key words and see how it changes our teaching:

Replace “teach” with “facilitate”. Let’s think about enabling a shared journey capable of enabling individual exploration. This is not top-down teaching where the teachers knows and the pupil’s don’t yet know. This is the teacher creating space (within a structure) for children to discover. The teacher can model discovering too – that’s very powerful.

Replace “knowledge” with “experience”.