How Tiny Art Schools Grow

Paula Briggs, Co-Founder, CEO & Creative Director of AccessArt explores the importance of the AccessArt Tiny Art School Movement and shares her own Tiny Art School experiences.

Apologies for the photo quality – many are copies of analogue images from many years ago.

“My own tiny art schools have formed and reformed themselves over the years, taking on the shapes that were right for me at the time. Sometimes they have lasted just a few weeks, appearing as an idea and dissolving when funding or energy stopped, and at other times they have lasted for years, creating their own energy and momentum to drive them into things which were much bigger than I could ever imagine.

During the final year of my BA Hons Fine Art in 1990, at the then Norwich School of Art, I began to think about what was next. Even at that time, opportunities for graduates to find work as visiting tutors were very limited, and I had the strong sense, right from the start, that I needed to create my own work, rather than rely on applying for external opportunities. So, during my last term, as I was putting together my degree show, I also started to make enquiries back in my home town of Sheffield, thinking about how I could share my skills as an artist, and create a small income for myself in the meantime.

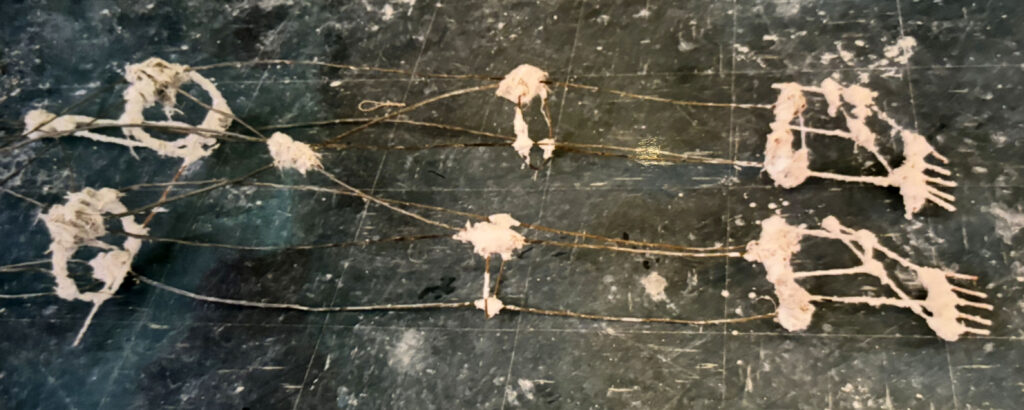

Of course, there was no internet, and I can no longer recall the lengthy, drawn-out processes I must have gone through to find an audience, a location and funding. I chose a city farm on the edge of Sheffield, and I offered my skills as a sculptor working over a few weeks with a group of children from an inner-city school. We drew and we made – and because I had no experience of running workshops, I was of course overly ambitious. 30 children made large clay birds, which I made plaster moulds from, casting each bird in cement. When the children visited again, reunited with their transformed birds, they were painted in acrylic and varnished, to make a flock. The physical work was exhausting, but it was the first time I experienced that amazing feeling of changing someone’s day-to-day experience of life. The experience came in the form of a small boy called Wesley – someone who until the workshops, had not found a way to shine. But he shone – and he knew he did.

The funding for the workshops had come from some local authority arts grant I think, but it was very modest, and I ended up paying a college friend to help me with the casting as I couldn’t do it alone. I would have been financially better off taking a job in a bar or café, but I remember the feeling of satisfaction and identity I experienced after the workshops. As the friend and I sat in the pub, exhausted, sunburnt and covered in plaster, the sense of value and connection was huge. That feeling, fleeting as it was, sunk into my bones, and drove me forward.

There were more workshops in more venues. In the 90’s there were small amounts of cash floating about – always hard work to apply for, but I didn’t mind that. Most of my graduate friends were on the Enterprise Allowance Scheme – a government initiative that meant you could claim £40 a week for a small “enterprise” rather than claim a similar amount for looking for work. This meant that artists could, with all honesty (and great modesty) set aside time to explore options. I was also awarded a grant of £1500 from the Princes Youth Business Trust. My business plan was as an artist educator – and I spent the money on an Amstrad computer to write my letters of application and proposals, and a bandsaw.

My forays into artist-led workshops were put aside whilst I undertook my MA at the Royal College of Art, but it was my time at the Royal College that affirmed to me that the connection with people who might describe themselves as not being artists, was vital. The Royal College at the time felt like a hermetically sealed unit, for Fine Artists anyway, where you were expected to make work which was understood (or not) by other artists. It stifled me. I couldn’t keep up, and my ego took a shot. I came away with the exact opposite feeling that I’d had after the long, hard workshop day – this time one of lack of purpose, lack of place. What use were my philosophical and artistic ramblings to the world? I couldn’t see it.

More workshops, this time through a residency I set up for myself in Chiswick House and Gardens. More local authority funding. More contact with not only young children, but also appreciative older ladies. My sense of worth slowly rippled around the edges.

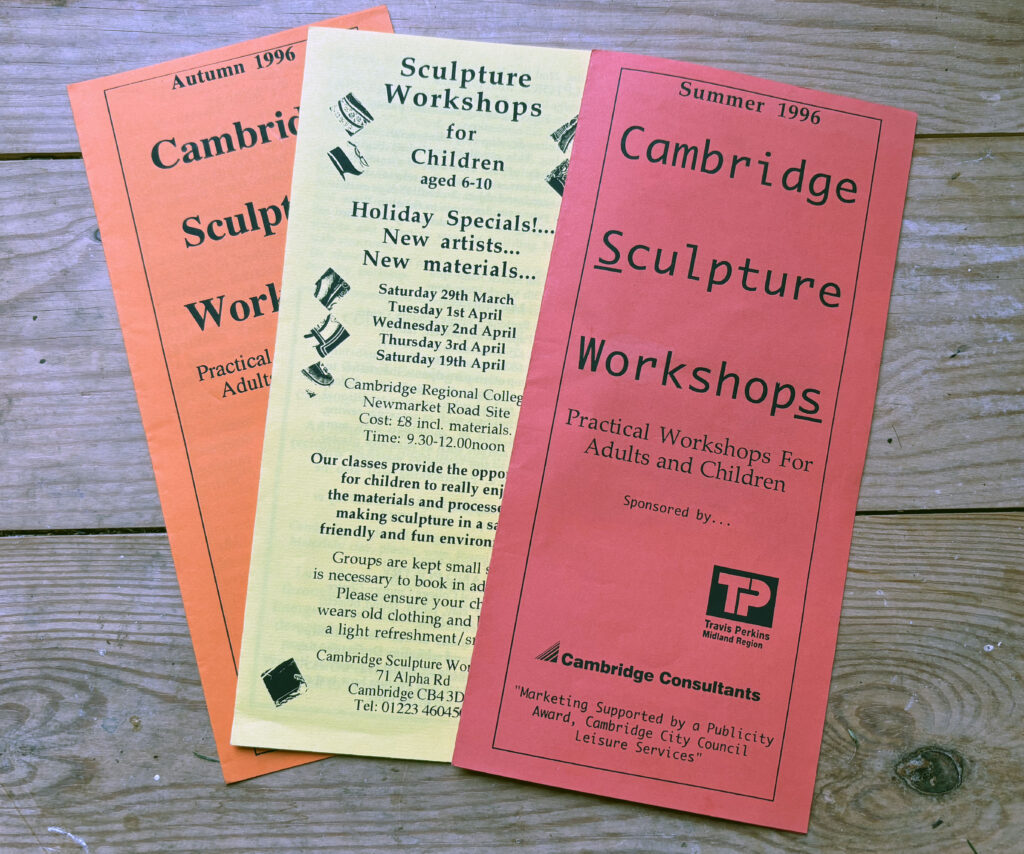

A move to Cambridge in 1995, (thank you world for the synchronicity), meant I was living in the same town as Sheila Ceccarelli, house mate and soul mate whilst we were at the Royal College of Art. Both of us were struck by the same post-RCA malaise. We sat down together in Sheila’s kitchen, to plan. No more alone, no more just me, now the two of us planned together. An organisation emerged: Cambridge Sculpture Workshops. We drew our logo with a mouse on Sheila’s old Mac, sitting next to each other. We wrote our sentences together, one dictating, one typing. Incredibly frustrating, and slow. But it was like we were holding hands, giving each other confidence to re-emerge. We applied for funding – Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, local authority, National Lottery, Arts Council. Small, small pots. We networked – councils, museums, galleries, schools. And we lugged our stuff – Sheila’s car heaving with tools and materials.

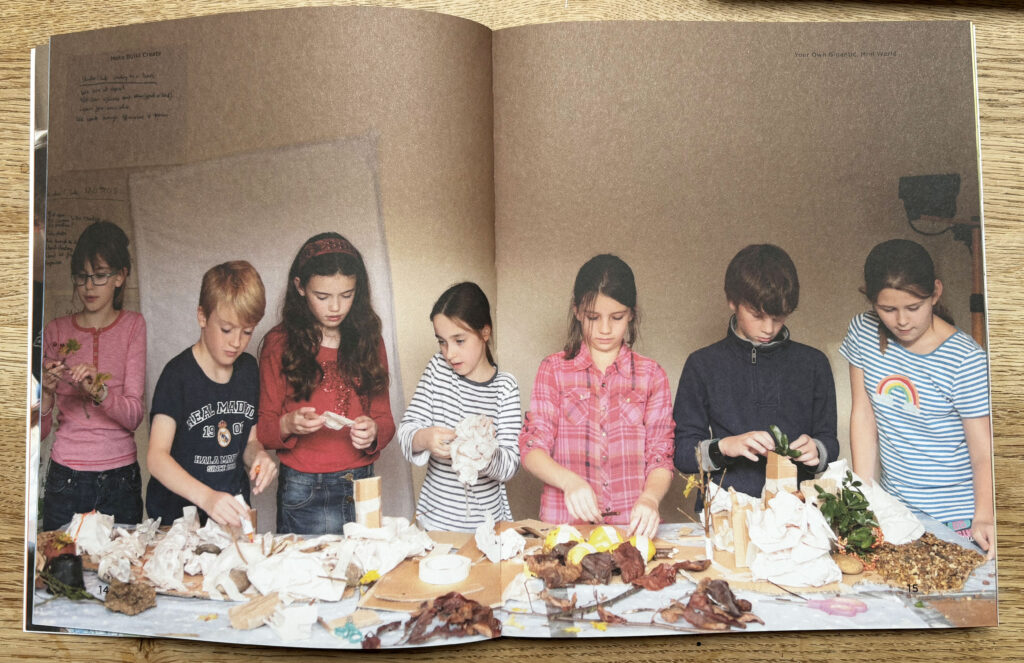

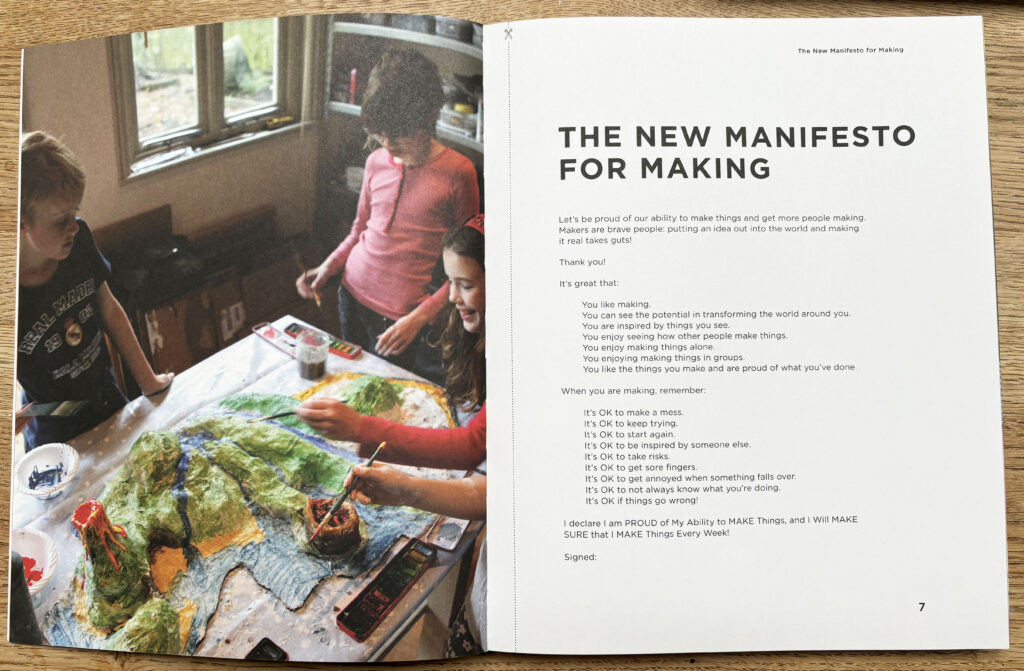

Kettles Yard allowed us to turn their education room into an 8 week sculpture studio, and workshop participants visited and traipsed their plastery feet back through the gallery. We ran regular sessions in other venues for all ages, offering children time and space to make a mess, and offering the middle-aged ladies of Cambridge Saturday art schools which they attended for all kinds of reasons. Lots, and lots, and lots of workshops in schools. And we built a Guy for the city bonfire, in a shopping centre with children and families, and we watched it burn, leave the fire, and float dangerously over the heads of the gathered bonfire night crowd (in 1996 there were few risk assessments, apparently). We learnt our craft, and we learnt how important it was to help provide opportunities for people to come together to make.

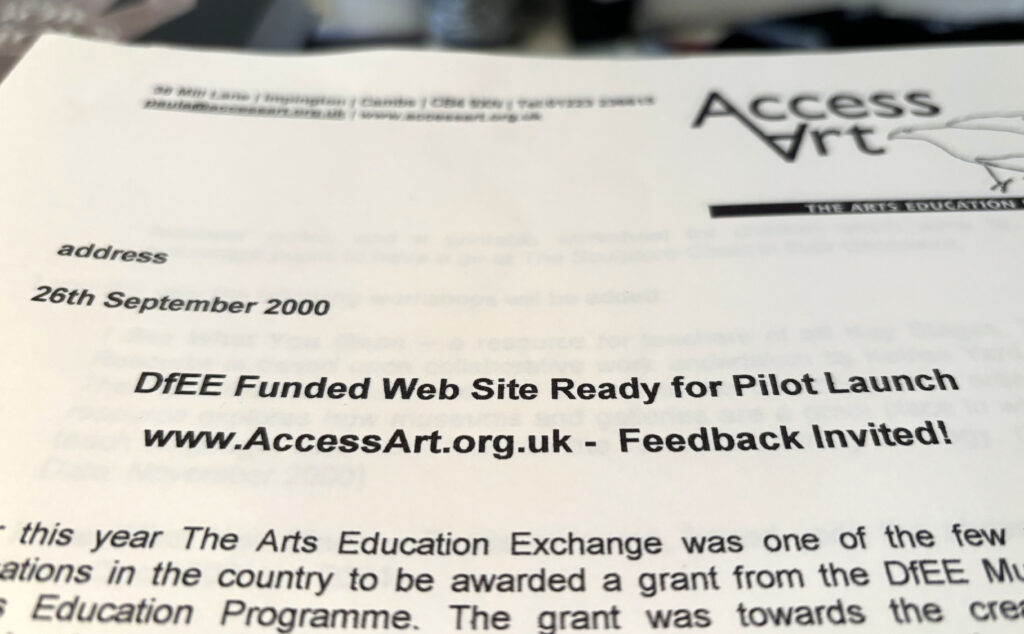

AccessArt emerged from Cambridge Sculpture Workshops, giving us new opportunities to try different models of tiny art schools. Sheila and I had children of different ages, and we both had busy schedules (AccessArt was always woven around family), so we decided to divide and conquer – she would run workshops for children her daughter and son’s age in one part of Cambridge, and I would workshops for children of my daughters age in another. And so began my own daughter’s art education, at the age of four, as I designed and ran sessions based around what I thought she and her friends would enjoy. Income from the sessions was small (I think we charged £9 for an hour-long session, had no more than ten children, and paid rent to the village hall). But learning was intense, for me as well as the children. Better still, Sheila and I would return from the sessions, write up what we did, and share it on AccessArt for the other to see. And there was the beginning of the posts you see on AccessArt today. Suddenly the “value” of each session was enabled to grow – not just benefiting the children that attended, but also those that read about the ideas after the event.

As I realised a pedagogy was forming, I felt enabled to write books which further shared the ideas. Again, lots of learning, but always the feeling that to create income (this was at a time before AccessArt was able to pay Sheila and I a wage) we had to maximise in as many ways as possible our knowledge and experience: event, resource, book – all made sense.

Through always responding to what I felt the children and young people I met needed, new ways of creating tiny art schools emerged. When my daughter was 12, and she and her peers were one by one dropping primary school hobbies, the teenage Be A Creative Producer project began as a way of helping them explore how valuable their creative skills were, and how powerful collaborative working could be. For nine months the five teenagers came back to the house every Friday after school, and we turned the dining room into a studio where we animated, made sculptures, films and music. It was an intense and incredibly productive experience, which looking back I now see I could have only done with 12 year olds – any younger they wouldn’t have been ready for it, any older they would have resisted it – but it leaves an amazing legacy.

My latest tiny art school format is, I guess, our Substack-based Everyday School of Art which my daughter and I write together, as a way of exploring personal creativity as well as the importance of art education. And the other tiny art school – AccessArt itself!

So, a few tips, thoughts and opportunities for any artist educator interested in their own re-inventions of tiny art school formats:

- AccessArt will help you where we can. The site is full of ideas to inspire your teaching. We are also in the process of creating case studies of the many ways other artist educators are running their own tiny art schools, and resources which share practicalities. Keep in touch via this page.

- Remember (or know for the first time), that your skills as an artist educator are SO unique and valuable. Through working you will become to recognise that, as you see the effects of your work on others. Be proud about who and what you are, share your good energy, and trust your instinct.

- Spin around. Look behind you, to the side, in front, up, down. Don’t assume you know where you’ll work, who you’ll work with. Maximise the results of any opportunity by writing and sharing. Think what you can do around the actual thing itself.

- Keep re-inventing yourself, or what you do. Don’t be afraid to stop, start, and make things fit in with your life. All the different experiences will ultimately weave together to form your unique offering.

- It’s easy to want to hug the hard-earned experience to yourself, holding it tight so no one steals it, BUT you end up getting so much more back by sharing where you can, and in so doing building your reputation as an expert. Enjoy the momentum as it snowballs.

- Find a friend. Collaboration has always helped me. Doing things alone, at the right time, has also always been enabling. But networks and communities are of course good – so seek them out – or make them.

- Finally, be practical, but be philosophical and aspirational – let small ideas land in your head and don’t talk them down. Don’t talk yourself out of things. Talk other people into things.